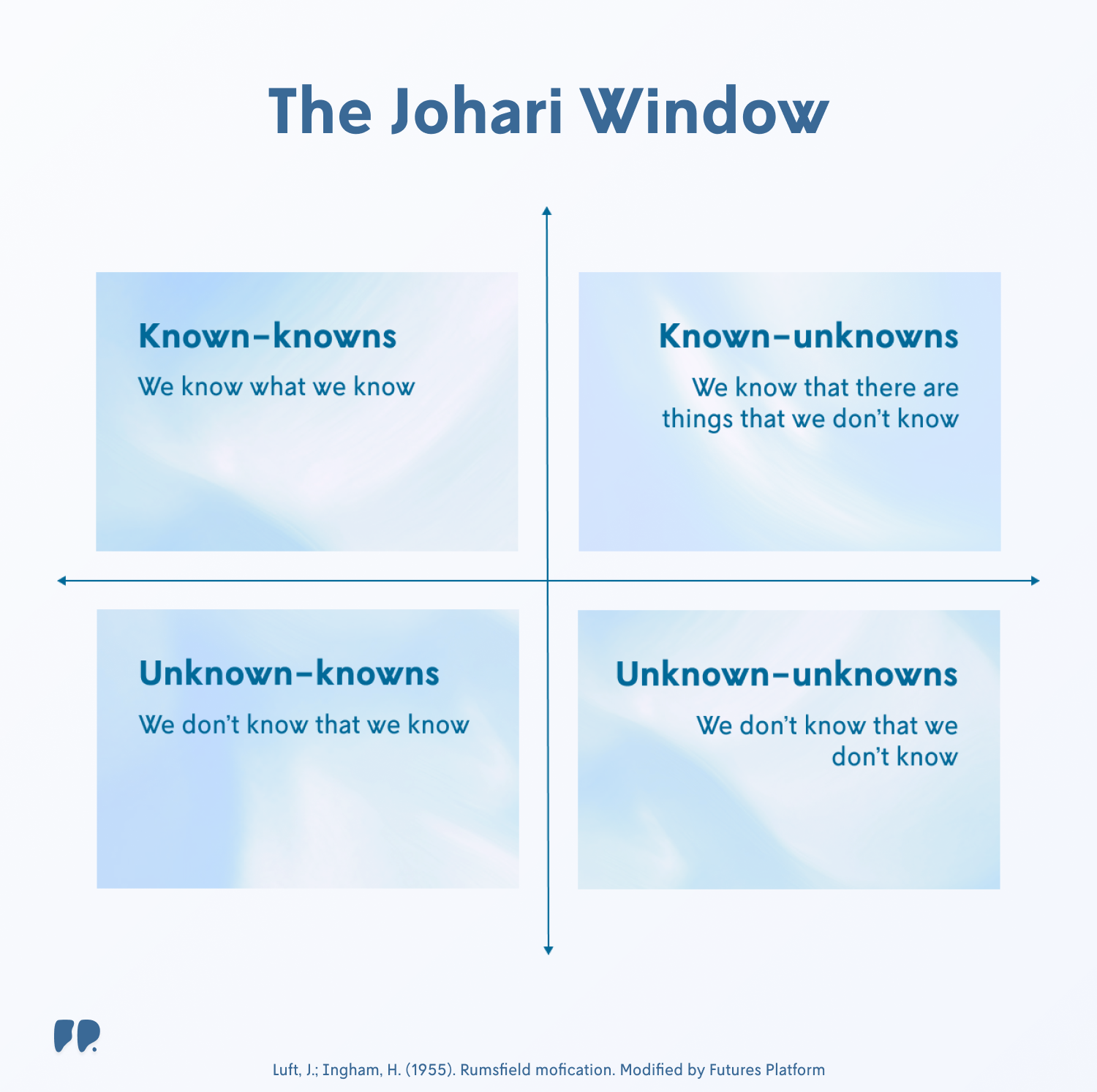

The Johari Window: Exploring Futures from Four Different Angles

The future is a mix of what we know is coming, what we can anticipate but not fully see, what we overlook despite being right in front of us, and what blindsides us entirely. The Johari Window maps the future across these four lenses: the known, the uncertain, the overlooked, and the unimaginable.

FUTURE PROOF – BLOG BY FUTURES PLATFORM

We all know the future is coming. But we don’t know exactly how, when, or with what impact. Some changes are clear. Others we sense but can’t define. And a few will hit us completely by surprise.

The Johari Window provides a structured approach to exploring the various types of knowledge we have (or lack) about the future. Developed in 1955 by psychologists Joseph Luft and Harrington Ingham, the framework was originally designed to explore self-awareness. Later, it was adapted for strategy contexts by former U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld.

The model maps four quadrants of knowledge: what we know, what we don’t, what we overlook, and what lies beyond imagination. Each quadrant opens a different way of engaging with the future.

Known-knowns: The base of certainty

Known knowns are the things we can point to with confidence. Megatrends, trends, market data, facts, and laws all fall into this quadrant. They are often quantifiable and widely documented.

Known knowns form the solid ground we stand on when making decisions. For example, knowing a competitor has just entered a new market, or that e-commerce sales have doubled over the past three years.

Yet even here, perspective matters. How we interpret what is known can influence the choices we make about the future. Two companies may see the same trend but act very differently. Methods such as trend extrapolation, trend impact analysis, and mapping change drivers turn raw information from ‘known knowns’ into actionable insight.

Example: A retailer sees that online shopping is surging (known known) and chooses to expand its digital presence—but the way it integrates delivery and in-store experience will determine the success of that move.

Known-unknowns: Preparing for uncertainty

Known unknowns are the uncertainties we can clearly name but cannot pin down. We know AI will reshape industries; we know climate change will alter everything from ecosystems to economies. But the exact form, timing, and ripple effects remain elusive.

This quadrant asks us to hold multiple possibilities in view at once. It is about preparing for several plausible futures at once, rather than betting on one. Methods like scenario planning are commonly used to explore the known unknowns.

Example: A logistics firm recognises autonomous vehicles are on the horizon (known unknown). What it cannot know is the adoption curve. By running multiple scenarios—fast adoption, slow adoption, regulatory delays—it can invest strategically rather than gamble blindly.

Unknown-knowns: Hidden in plain sight

Unknown knowns are the signals right in front of us that we somehow fail to register. They are too close or too familiar to see directly—the subtle shifts, early signals, and emerging patterns we dismiss as noise until they suddenly change the game. More often than not, they only become obvious in hindsight.

These blind spots are often cultural or behavioural. The challenge is not spotting everything, but questioning the patterns we take for granted and asking whether they carry more weight than we assume. Methods such as weak signals analysis, emerging issues scanning, and signs of discontinuities help detect these subtle shifts.

Example: A grocery chain notices more customers asking about plant-based options (unknown known). For years, it treats it as a niche preference. By the time plant-based eating becomes mainstream, competitors who acted early dominate the category.

Unknown-unknowns: Imagining the unimaginable

Unknown unknowns are the most challenging category. By definition, they are events or shifts so far outside our mental map that we do not even realise we should be paying attention. Most are considered impossible to anticipate, let alone predict.

The goal is not to spot them in advance, but to stretch thinking into uncomfortable territory and stress-test strategies against the seemingly impossible.

Methods such as science fiction prototyping, wild card analysis, and visionary scenario exercises allow organisations to explore radically different futures, which can inspire breakthrough products, services, or systems that would have once seemed impossible.

Example: A biotech innovation makes ageing itself treatable as a disease, extending healthy lifespans far beyond expectations and disrupting everything from pensions to family structures.

Learn how to prepare for uncertainty in a structured way

Get your free copy of our step-by-step guide to scenario planning and build winning strategies that can thrive across multiple possible futures.

Before the world caught on, Givaudan was already designing the taste experiences of tomorrow. We sit down with Igor Parshin, Customer Foresight Lead at Givaudan to talk about how the company uses foresight to turn early change signals into the flavours that will define the future.