Why did we have such positive faith in the future in the 1960s-70s, but now just fear for the future?

What can generational theories tell us about this shift?

Epoch Change blog series, No. 3

Dr. Tuomo Kuosa

Tuomo is co-founder and Director of Futures Research at Futures Platform. He holds a PhD from the Turku School of Economics and is an Associate Professor (Docent) of Strategic Foresight at the Finnish National Defence University.

FUTURE PROOF – BLOG BY FUTURES PLATFORM

John F. Kennedy (US President 1961-1963) is famous for his super-ambitious projects and urge to push the nation toward greatness. For example, the "We choose to go to the Moon" speech of 1963. Lyndon B. Johnson (US President 1963-1969) is famous for his optimistic quotes regarding our ability to forge the future according to our wishes. For example, "We have the opportunity to move not only towards the rich society and the powerful society, but upwards to the Great Society."

Yet, for some reason, over the past couple of decades, we have had only fear for the future and a desire to go back to the glorious past. Why is that, and how do generational theories such as Strauss and Howe's theory or its predecessors, like Ibn Khaldun, explain this?

Generation theories are one of the retroaction modes that have been used to explain the cyclical and recurring nature of societal change. Here, the basic principle is that a generation is a demographic cohort that shares an age location in history and, therefore, encounters similar historical events and social influences during the same life stages. Especially the formative years around young adulthood are crucial in the process of forming a shared generational experience, including perceived social identity, common beliefs, behaviours and even an entire shared worldview.

Ibn Khaldun's (1332-1406) father-and-sons model has been especially used to explain the war-peace cycles and may be considered one of the predecessors of modern sociological generation theories. It describes how "asabiyyah", the group feeling or social cohesion, changes from generation to generation in a recurring pattern. Naturally, this theory too has predecessors such as Sima Qian's (Szu-Ma Ch'ien, 145 BC - 86 BC) and other ancient Chinese studies on the topic.

Societal turnings and generational identities

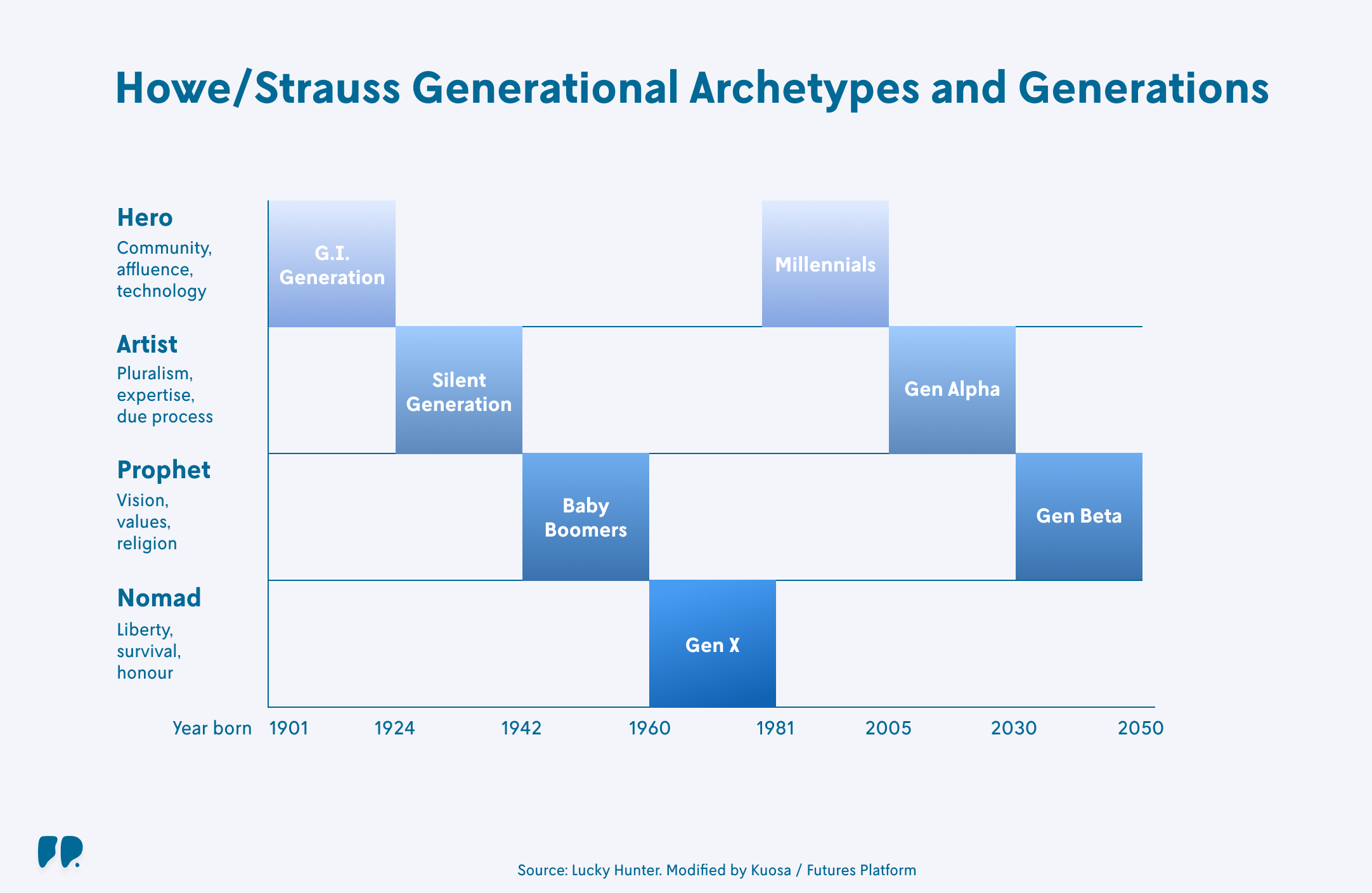

One of the most famous generation theories in modern sociology is Strauss and Howe's theory (1991-1997, 2023), which generalised the concept of 'generation identities' and generational archetypes, namely prophet/idealist, nomad/reactive, hero/civic, and artist/adaptive.

These archetypes arise from recurring turnings, such as social mood and value changes and pivotal shared generational events that forge the generational experience. Each societal turning lasts ca. 20 years, and the four turnings together form a ‘saeculum’, meaning a societal cycle, that lasts ca. 80-90 years. Hence, Strauss and Howe discovered that there has been a phase of national crisis in the United States every 80-90 years, and halfway between these crises, a cultural awakening has occurred.

The Strauss-Howe generational theory is a strong generalisation of how generations are forged and how similar generational moods recur throughout history in quite fixed intervals. However, the weakness of the theory is its US-centricity: it focuses only on US history since the beginning of the 18th century. This leaves much room for speculation as to whether the same findings apply globally or in prior centuries.

From the point of view of macrohistorical analysis, the most valuable takeaways of this theory are the turnings and generation shifts relationship, which gives us one type of retroaction model. The generation's length is quite standardised due to biological reasons. Each turning emerges from the power of generations who have been forged into a shared identity and worldview during the ongoing and previous turnings. Once a new generation is finally forged and comes into adulthood and power, it begins to reform the societal realm, which in turn leads to the next turning.

Strauss and Howe's recurring societal turnings and the related forged generations are the following four, each lasting approximately 20 years:

The High

This societal period is characterised by strong institutions, social collectivism, community cohesion, a strong social order, and weak individualism. It comes after the crisis that ended the previous cycle. The generations born near the end of a crisis and during a time of societal High are called Prophet/Idealist. They are described as indulged children of a post-crisis era. Prophets are believed to grow up as young "hippies" or crusaders who want to shake society’s morals and principles in middle life.

The Awakening

This societal period is characterised by the increase in people's personal and spiritual autonomy. Social institutions may be attacked during this period, impeding public progress. The generations born during an awakening, when crusader prophets are attacking the status quo and its institutions, are called Nomad/Reactive. Consequently, they are described as growing up under-protected and alienated in social chaos. Nomads are believed to grow into pragmatic and resilient adults.

The Unravelling

This societal period is typified by weak institutions that are distrusted. During this period, individualism is strong and flourishing. The generations born after an awakening, during an unravelling, when social institutions are weak, and individuals have to be self-reliant and pragmatic, are called Hero/Civic. They are more protected than the children born during the chaos of an awakening. Heroes are believed to grow into young optimists who are energetic, over-confident, and politically powerful adults.

The Crisis

This is a societal era of destruction, e.g., through war, where institutional life is destroyed. However, as this period comes to an end, institutions will be rebuilt. Society will rediscover the benefits of being part of a collective, and community purpose will retake precedence. The generations born after the unravelling, during a crisis, when external dangers recreate a demand for strong social institutions, are called Artist/Adaptive. They are believed to be overprotected by parents who are preoccupied with the risks of the crisis. Artists often grow into conformist and process-oriented yet thoughtful adults with more traditional values.

Optimistic and pessimistic expectations of the future

Going back to the opening question – why did we have such a positive faith in the future in the 1960s-1970s but now just fear for the future? Furthermore, why did we have the Annus Horribilis of 1968, the year when the world seemed to have become crazy?

The year 1968 and the short period surrounding it were a time of sociocultural revolution in the West, as discussed, for example, by historian Professor Laura Kolbe (2008). Various social values went into turmoil. The contraceptive pills had just become available to all women, which led to sexual emancipation and demands for equality between the sexes. Also, LSD and other drugs, and for example, Jimi Hendrix's music, spread through the US.

All these drove the flourishing of the hippie movement with the slogan "Make love, not war", but also to something that was called the liberation of the mind. The liberation and the related cultural shock were multiplied and spread rapidly throughout the US, as 1968 was also the turning point of the mass media. The new TV era enabled most people to witness firsthand all the ‘crazy things’ unfolding in the world. It also motivated many to join the protests and riots. As a result, the zeitgeist change was swift and enormous. First in the US, but soon after elsewhere, too.

Strauss and Howe's theory provides an excellent foundation for explaining this. The years 1943–1960 were a time of High when the US became a world superpower. Builder and problem-solver presidents like Harry S. Truman and Dwight D. Eisenhower set up the US-led, rules-based international order through initiatives like the Marshall Plan and the creation of institutions such as the United Nations and NATO. This was the time when the prophet/idealist generation came to power in the US.

The High was followed by a time of Awakening (1961 to 1981) in the United States. This period was marked by a consciousness revolution, as personal and spiritual autonomy gained prominence. It was a time when social institutions could be attacked, impeding public progress. At the same time, it was also a period of bold and optimistic visions for the future. For example, President Kennedy famously declared, “We choose to go to the Moon,” and President Johnson envisioned, “We have the opportunity to move not only toward the rich society and the powerful society, but upward to the Great Society.”

Contrary to the optimism of the 1960s-1970s, the recent era, which began around 2005, has been a time of crisis. In my view, it is naturally a period when the future must seem scary. The past appears glorious, and there are no optimistic future visions by definition. The time of optimistic future visions will come, but probably not before the 2050s, as there is a period of High coming before it.

The High of 2030-2050 will be about rebuilding, strong economic growth and the establishment of new institutions, Empires, economic ecosystems and social cohesion. During that High, Generation Beta will be born. It will be our next idealist/prophet ”Hippie” generation who will dream big and shake the ethical foundations of society. I will get back to this topic in my forthcoming blogs, taking a more holistic perspective on the forthcoming epoch change.

This article is the third instalment in Dr. Tuomo Kuosa’s Epoch Change series. You can find the other articles in this series listed below:

The Shift in Technological Platforms and Business Ecosystems Over Time

Why did we have such positive faith in the future in the 1960s-70s, but now just fear for the future?

From Chaos to Order: What Nature Can Teach Us About Societal Change

Are there five, six or even more different lengths of societal cycles?